Stalemate State

STALEMATE STATE

Illustrations by Lily Oberstein

The race to win Wisconsin and the presidency

On Nov. 8, 2016, Donald Trump shocked the world and won the presidential election, and Republicans won every statewide election in Wisconsin that night.

“It was like the floor fell out and we were suddenly falling into a bottomless abyss,” says Ben Wikler, now-chair of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin. “That was one of the darkest nights of my life.”

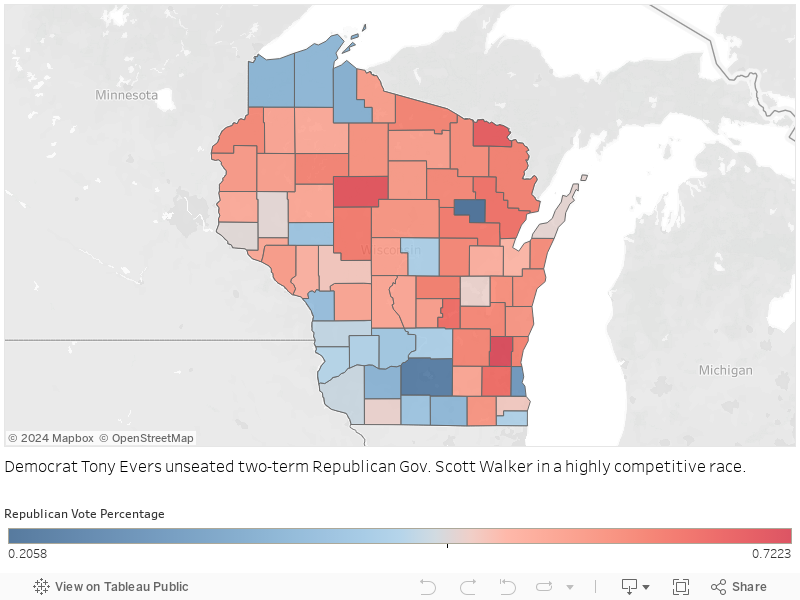

On Nov. 6, 2018, State Superintendent Tony Evers unseated two-term incumbent Republican Gov. Scott Walker after a dramatic late-night victory. Democrats won every statewide election in Wisconsin that night.

“There was a new structure needed at that time,” says Mark Jefferson, who has been executive director of the Republican Party of Wisconsin before, and returned to the role after Walker’s defeat.

Two years apart.

Two dramatically different results.

Heading into the 2020 election, many political pundits agree that Wisconsin is the battleground where the presidential election is likely to be fought — and potentially won. But which direction the voters of Wisconsin will choose is far less clear.

With Wisconsin’s 10 electoral votes being decided by fewer than 23,000 votes in three of the last five presidential elections, Supreme Court seats decided by less than one point and a governor’s race decided by less than two points, the stakes are incredibly high. As voters navigate the 2020 election, the choices the two parties make over the next 11 months can be critical in determining which direction Wisconsin, and the country, goes.

A swing state

Democrats won the state’s electoral votes in every election from 1988 to 2012, but control of the governor’s office, other statewide offices and the state Legislature has swung between the two parties for years. After Trump’s victory, many claimed that something had fundamentally changed in Wisconsin and it could now be labeled as a swing state.

“I don’t think the change has to do with becoming a swing state. I think it was always a swing state,” says Craig Gilbert, the Washington bureau chief for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Gilbert has covered Wisconsin politics for more than 30 years. In that time, he says, elections have never truly been predictable or consistent in outcome.

“During that whole 30-year period, even though part of that time Democrats were consistently winning elections for U.S. Senate and for president, some of those elections were very narrowly won,” Gilbert says. “And Republicans were winning a lot of elections for governor, and in some cases the legislature and in some cases statewide offices.”

While outsiders may see the state differently after 2016, Wisconsin has seen plenty of divided government and close elections over the years. The makeup of the state itself has stayed remarkably consistent, according to Jefferson.

“Usually you see states changing over the course of a generation. It becomes more Republican or more Democrat. Wisconsin really hasn’t,” he says. “It’s just been right on that bubble now for a solid generation. And that’s not changing.”

County results of the 2016 presidential election

Close calls

Margins in statewide races have been incredibly close in the 21st century. In 2000, Al Gore won the state by only 5,708 votes, and the margin stayed close in 2004 with John Kerry winning by only 11,384 votes. And three of the more recent statewide races — governor, president and Supreme Court justice — have all been decided by less than two percentage points each.

While the state has remained close over time, individual areas have become less competitive. According to Gilbert, counties across the state have become more partisan in their voting habits.

“There are some Republican areas that have become more Republican and some Democratic areas that have become more Democratic,” Gilbert says.

Democratic strongholds like Dane, Milwaukee and Rock counties have become even more Democratic, while Republicans have seen their margins grow in northern-rural Wisconsin, and in the so-called WOW counties — Waukesha, Ozaukee and Washington — in suburban Milwaukee.

According to Charles Franklin, director of the Marquette Law School Poll at Marquette University, the balance between those counties has played a part in fostering close elections.

“Where the balance lies is what determines whether Evers wins by one or Trump wins by almost one,” Franklin says. “In that sense it’s a balancing act that crosses a whole bunch of places rather than being just in one place.”

That close balance is part of the reason why many have projected Wisconsin as being one of the most important states for 2020.

“At least for now, it’s a pretty solid claim that we are very close to the tipping point state as we understand the election today,” Franklin says.

Wisconsin was one of just a handful of states that were within five percentage points in the 2016 presidential election. In the race to 270 electoral college votes needed to win, the stakes are high for candidates to compete and win a rare up-for-grabs state like Wisconsin.

“Wisconsin gets you that 270,” Jefferson says. “If you’re right there, Wisconsin’s probably gonna be right there.”

Wikler predicts Wisconsin will be the “site of the biggest showdown in the history of American politics.” According to him, this gives the voters of Wisconsin great influence over the 2020 election.

“I think of it as a superpower,” Wilker says. “Everyone in Wisconsin has been given a vote that matters more than the votes of people in any other state.”

The strategies both parties employ, and the issues that resonate for Wisconsin’s electorate, may decide which direction the country goes.

County results of the 2018 governor’s election

2020 strategies

Wisconsin may be crucial to winning the presidency, but according to Franklin, there isn’t just one key to winning the Dairy State.

“If you look at stories, you will commonly see people write ‘the key to winning Wisconsin is,’” Franklin says. “We were decided by 23,000 votes, there must be two dozen keys to winning.”

In that type of environment, every voter — Democratic, Republican or independent — matters. According to Gilbert, recent elections have become more about turning out the “base” than those who need persuading.

“But that doesn’t mean [persuadable voters] don’t matter, and that doesn’t mean they don’t exist,” Gilbert says. “That obviously in a really close election they matter. It doesn’t take a lot.”

This presents a challenge for both parties, and given the back-and-forth of the past few elections, neither can afford to use the same playbook as the past.

According to Jefferson, the Republican Party has struggled to match “old-school retail politics” with more modern technologically driven grassroots approaches.

“I think the ground game is going to matter this time around,” he says. “We’re going to have to have had strong data. We’re going to have to have had a lot of volunteers on the ground using the latest data and tools.”

Jefferson says using more sophisticated data will help the party find voters and tailor messages specifically for them. Among the voters Jefferson hopes to reach are Republicans living in Democratic areas, Republican voters who simply need a motivation to vote and likely voters whose choice is unclear. Once they find the voters, communication becomes critical.

“If you’re talking to voters, you can dial down a lot of the animosity, a lot of the rhetoric that you see on cable news all the time, by just being a neighbor talking to a neighbor and having a discussion,” Jefferson says. “One by one, it makes a tremendous difference when you have a lot of volunteers out there doing the same work.”

According to Wikler, Democrats will also look to connect directly with voters in 2020. Their focus thus far has been building what Wikler calls “neighborhood teams.” These teams go out in their own communities and talk with voters to learn more about the issues people are focused on.

“The best messengers are the closest messengers,” he says.

The Democratic Party has been building these teams for the past two years, according to Wikler. For now, their emphasis is on hearing what voters have to say.

“Our focus right now is listening to people as opposed to telling people things,” he says. “There are millions of voters in the state and understanding what motivates them and what they care about and what their issues are is something we can do through the summer of 2020.”

Issues

Along with tracking head-to-head races, the Marquette Law School Poll asks around 30 questions to gauge opinions on public policy, Franklin says. In a recent poll, conducted from Aug. 25-29, Franklin pointed to economic opinions as something to watch ahead of the election.

While more respondents held a positive view of economic performance over the past 12 months, there is now a more negative outlook on the economy for the upcoming year.

“We saw economic optimism for the next 12 months, here in Wisconsin, turn negative for the year,” Franklin says. “And quite negative in our August poll, having never been negative throughout 2012 through 2016 with Obama, and having been even more positive under Trump in ’17 and ’18.”

Even as polls show a faltering sense of optimism in the economy, Jefferson says Republicans will look to tout its strengths during the election.

“I think the president has a great record to point to, and I think the things that we’ve done since he’s been president have helped … has contributed to that growing economy,” Jefferson says.

While Wikler acknowledges the importance of issues related to the economy, he says the No. 1 issue is health care and the cost of health care.

“Really health care is like in 2018. It’s the number one thing that people are feeling strained by,” he says.

While the two party leaders don’t agree on what issues will be most important, they do have one thing in common: They both share a sense of optimism about how it will turn out.

“I feel good about the 2020 election,” Jefferson says.

“I feel a combination of confidence and productive anxiety,” Wikler says.

Want more politics?

Click the button below to learn more about upcoming elections in Wisconsin.